Art and China After 1989 Theater of the World

Fine art and Red china subsequently 1989: Theater of the Earth

The curatorial mission, to showcase the influence on artists and their practice of two distinct moments of political impact – the Tiananmen Square crackdown and the failed promise of the 2008 Beijing Olympics – upends our understanding of the mod Chinese aesthetic

Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York

vi October 2017 – 7 Jan 2018

past JILL SPALDING

The break was defining and sudden. In 1988, a People's republic of china that had been opening to reform immune veteran artist Wang Guangyi to depict Chairman Mao behind bars. Two months into 1989, Beijing'due south National Art Museum of China mounted the China/Avant Garde Exhibition to parade its officially liberated visual art. 4 months later on, the Tiananmen Square massacre forced complimentary expression underground or into exile, where an intrepid grouping of artists recalibrated methodologies to claiming a newly repressive government'southward calumniating behaviour. Magiciens de la Terre , at the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Grande Halle de la Villette in Paris, had introduced Mainland china's provocateur exercise to the west with just three of them (Gu Dexin, Huang Yong Ping and Yang Jiechang) – all showing here. Far too few, as it turned out, since the nascent protestation was outshone by easier-to-love riffs on local bop and western pop – those colourful exist-aware-or-be-foursquare paintings collected and promoted by David Tang at his Cathay Club in Hong Kong, which first came, as they infiltrated collections away, to stand for People's republic of china at present. Even every bit the mainland's tightening command triggered stronger work, those large vibrant canvases – more accessible, more saleable – still constituted for the west the gimmicky artful.

Wang Xingwei. New Beijing, 2001. Oil on canvas, 200 ten 300 cm. Thousand+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong, By donation. Photograph: courtesy M+, Hong Kong.

Until now. Bypassing the sale-driven celebrity art stocking the vanity museums in favour of lesser-known conceptual and experimental work, this exhibition has the fresh feel of an eye-opener. Spiking attendance, it arrived with the baggage of brouhaha. After showing in Dubai, three works involving live animals triggered a frisson that rippled across the Atlantic to unleash a force field of acrimony threatening chaos and worse. A video of tattooed pigs copulating? Another pitting chained dogs confronting each other until close to collapse? A doomsday vivarium that releases reptiles, insects and crawlies to devour each other to extinction? Protestation congenital to a level that led the Guggenheim Museum's director Richard Armstrong to pull all three works before opening. That the extent of public outrage was underestimated reveals how inured the fine art globe inner sanctum has become to humanity's threshold of decency. That the venerable New York Times chosen the Guggenheim "badly mistaken" for its "self-censoring" decision shows how far free expression has batty to confound censorship with respect. Referencing equally backup the Brooklyn Museum's past refusal to pull The Holy Virgin Mary (1996), a work by British painter Chris Ofili involving elephant dung – a case of apples and oranges on a 10-to-1 calibration – only made the paper of record look fatuous. Wiser the position that prevailed in my small in situ survey: although the Guggenheim should take thought better of including cloth that presents abused animals as an fine art form, the ensuing public outcry, climbing to threats against staff, viewers, installations and the building itself, justified a change, both of heart and of mind.

Huang Yong Ping's excoriated vivarium, Theater of the World. Photograph: Jill Spalding.

Emptied of life, Huang Yong Ping'southward excoriated vivarium [Theater of the World] holds court here (information technology supplies the show's subtitle later all) as a far stronger metaphor. And you lot won't miss the others. There are almost 300 other works here by 71 artists, and the presentation is stunning. In no particular order, although the stated brief posits an evolution of sorts betwixt 2 singled-out events, the elaborately detailed schemes pitting art'southward resources against tyranny play out freely across the walls and floors of a ordinarily intransigent space.

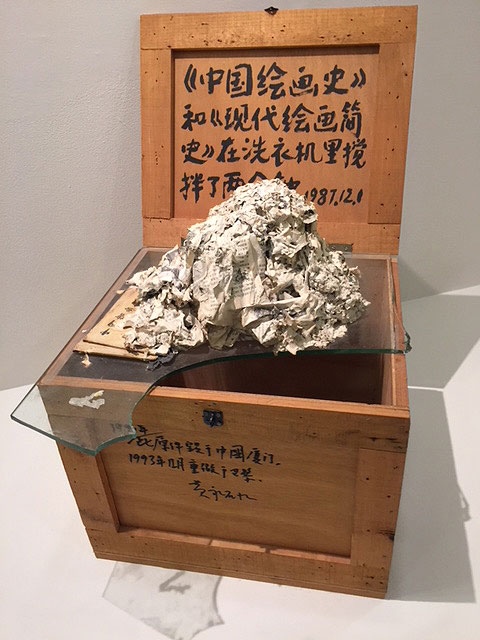

Seemingly organised according to which infinite best fits which work, the resulting presentation is less scholarly than revelatory. Wondrous the metaphor for cultural wipeout extracted by the aforementioned Huang Yong Ping from a glop of paper that had held the history of Chinese painting until run through a washing automobile (The History of Chinese Fine art and A Curtailed History of Modernistic Painting Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes, 1987/1993).

Huang Yong Ping, The History of Chinese Painting and the History of Modernistic Western Art Washed in the Washing Machine for 2 Minutes, 1987. Photograph: Jill Spalding.

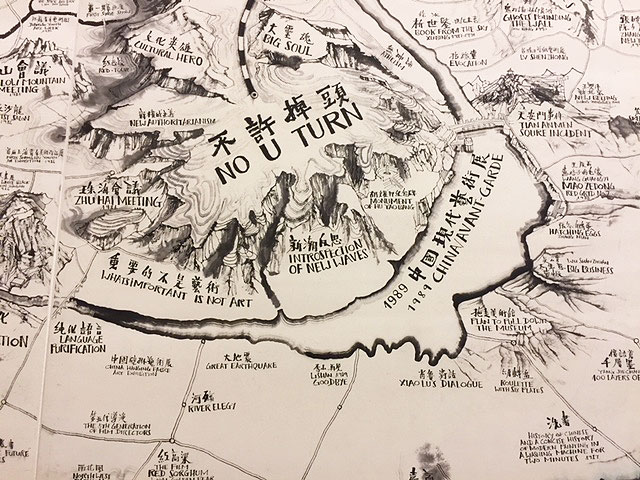

Spooky to segue from bodily drawers displaying didactic pamphlets to Jiang Zhi'south visceral print of a drawer containing the owner'southward severed limb (Objects in Drawer,1997). Gripping to movement between primary calligrapher Qiu Zhijie's magnified Map of the Theater of the World (2017), a tour de force manipulation of China's geography to parody power game strategies, and his single sheet of paper inked over for a year with the same ancient text to produce an indecipherable monochrome.

Jiang Zhi. Object in Drawer, 1997. Photograph: Jill Spalding.

Qiu Zhijie. Map of Art and China later on 1989: Theater of the World, 2017 (detail). Photograph: Jill Spalding.

Painting, though not the dominant medium here, is forcefully represented. The versatile portraitist Zhang Xiaogang borrows from photographs and western symbolism to mark citizens betrayed. The academically trained Zhao Bandi, although best known as "the Pandaman", here tilts realism – his canvas literally askew – to portray the spent illusion of a white-neckband life.

Zhao Bandi. Young Zhang, 1992. Oil on canvas, 214 x 140 cm. Installation view. Photograph: Jill Spalding.

Liu Xiaodong's mastery of perspective imbues a seemingly too-literal message painting, Burning A Rat (1998), with spine-tingling foreboding, and escalates induct despair through serial portraits of soldiers – they're so young! – from his eighteen-panel Battlefield Realism (2004). Shen Yuan has such a way with the castor that her delicate watercolours hold more than weight than the video interviews they support. And happy the mark-making technique of Yu Youhan and Ding Yi, abstract artists who employ astute interventions of shading and colour to give charted statistics centre-popping effects. Factor in an extra ten minutes to fully navigate Splendor of Sky and Globe (1994-5) – Liu Dan's spectacular reimaging of the landscape painting undertaken by the well-nigh accomplished of the majestic courtroom painters and indeed the emperors themselves – information technology will take your breath abroad. And that inkwork! One of those Pompidou "magiciens", Yang Jiechang yanks calligraphy from the confines of a scroll to a gestural majesty that envelopes a whole wall in the Tiananmen bloodbath.

Qiu Zhijie. The Present Continuous Tense, 1996 (reconstructed 2017). Photograph: Jill Spalding.

Interactive material is deficient (just here? or does information technology not speak to the Chinese soul?) but compelling; I had to line up to play Cao Fei's move-the girl-through a never-catastrophe fairytale videogame, and a small crowd formed in forepart of Qiu Zhijie'southward The Present Continuous Tense (1996), 2 gaudy funerary wreaths projecting the cheery smile of sunflowers to draw visitors in to a hidden photographic camera loop that captures them unwittingly looking upon their own decease.

Video work is plentiful and achieved; making full utilize of the space, curatorial ingenuity suspends, floats, anchors and bunches information technology. About instructive for the west, nigh none involve algorithms. And but one is digital – Cao Fei's masterful RMB Metropolis (launched in 2008, information technology's a virtual city she created in online game 2nd Life), designed by her avatar Communist china Tracy to projection a futuristic, rich-is-glorious, megalopolis that volition ascension on razed housing to profile China's side by side Olympics. Like weather – notoriously hard to convey in a video game – in a world of real consequences, the climate of oppression relies on reportage. How it is relayed is the fine art. Building to terror, the eponymous video, Kanxuan! Ai! (1999) follows the young artist fleeing an unspecified demon. Chen Chieh-jen's magnified shades-of-gray study of a wearable mill tracks the quiet despair of life tied to a sewing machine.

Well-nigh here are veterans.

Zhang Peili. Uncertain Pleasure ll, 1996. Six-channel, 12-part stream. Installation view: Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, October 6, 2017—Jan 7, 2018. Photograph: Jill Spalding.

Held to be China'south video pioneer, Zhang Peili'south Uncertain Pleasure ll (1996) works the small-scale screen into metaphors for anxiety with a six-channel, 12-role stream that magnifies easily scratching various torso parts raw. Zhao Gang'due south insightful The Harlem Schoolhouse of Socialist Realism Study (2002) – if y'all accept the 46 minutes to stay with it – brings the cultural revolution to an American working-class kitchen. Nosotros identify readily with these narratives – perhaps considering their makers lived away, often collaborating with western artists who hadn't still self-identified as collectives, but shared a "transexperience" of culture and a global consciousness.

Notwithstanding seeking Communist china? Individually, much of the émigré piece of work feels appropriated – Li Yongbin's video imposition of one face on another, Zhang Hongtu'southward Berlin Wall comment, and a forged invitation to participate in an exhibition were commencement explored in the w. The ultimate reveal is not visual. More than enervating of your time and almost impossible to digest, the defining material and real meat of the prove is the straight-out conceptual work, fully conveyed here through collectives. A deadening concept when associated with socialism and group-speak, these alliances enabled Chinese dissidence to emerge from the shadows every bit a powerful art class that western artists are simply get-go to fully mine and master. Albeit loosely affiliated, and whether for rubber in numbers, affordability or to slyly invert bureaucracy's thinking-past-camel, a majority of the artists who bankrupt through to the big time began with, or returned to, group statement. From a western perspective, the resulting efforts are astounding but abstract – a benefaction for sales of the museum catalogue that constitutes an exhibition on its ain.

Conceptual work enfolds traps. Even to understand the contribution of six artists to the Happiness Pavilion project from the small rock, wood and bamboo model on show is challenging: to follow the convoluted thinking behind the large storyboards is like crawling down rabbit holes. The amount of archival material – displayed here in the pullout drawers of chests that are scattered throughout – is in itself significant simply defeating. So how to absorb the cyberspace platform Art-Ba-Ba's 433-artist, 167-result, 10-twelvemonth-long projection from the documentary videos streaming on a series of tablets? What to brand of the detailed 1998 proposal for The Long March Project, which enacted a curatorial experiment by founder Lu Jie and creative person Qiu Zhijie involving thousands of participants, exhibitions and performances staged along the Red Ground forces's route to collectively "reinterpret historical consciousness and develop new creative approaches to political, social, economic and cultural realities". Moving along to Age of Empires – Zheng Guogu'south elaborate transposition of the famed getaway of literati from a repressive imperial court to a courtyard-landscape inside a vast architectural complex that he shaped with his Yangjiang Group into an imagined paradise – well, I just gave up and enjoyed the greenery. Ai Weiwei's wallpaper coil-out of citizens trapped in an earthquake; the myriad-artist Shanghai Contemporary Art Archive Project After 1998, and Ou Ning'south Heed Map of Bishan Commune (2017) – all elaborate subversions of numbing commercialisation, environmental degradation and aborted social activism – in turn numb the viewer. Notwithstanding, such is their latent power and brilliantly curated installation that emotion builds. Tedious as life-draining opioids, even the works that span yards of walls with the obsessive statistics and directives of unbridled oppression starting time to piece of work on you similar the baste-baste abuses of communist rule that disregarded, disrupted, and destroyed entire communities – day later day, year later on yr.

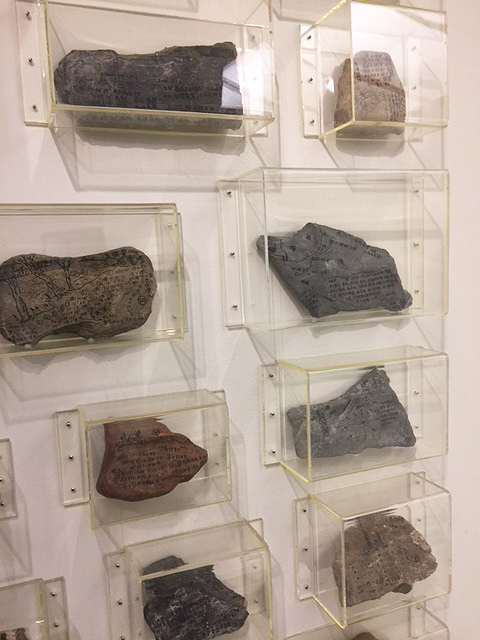

Song Dong. Throwing a Rock - Documentation, 1994. Ink on stone, 15 parts. Photograph: Jill Spalding.

More moving in the end, though, are the intimate protests. Literal works addressing capture and imprisonment with chain-link fencing, plastic tanks and nailed boots fan out to the purely conceptual statements of stones that once served as building blocks now framed past Song Dong's 1994 (Throwing a Stone – Documentation) as projectiles; Yang Fudong'south 1993 marked-up photocopies documenting with hand gestures his iii weeks without speaking; Lin Yilin's 1995 triple-entendre colour video, Safely Maneuvering Beyond Lin He Route, of a tourist photographing a worker building a wall for the land to confine him, who really might exist the creative person building a wall that art can dismantle; and Kwan Sheung Chi'southward A Flags-Raising-Lowering Anniversary at My Dwelling house'southward Apparel Drying Rack (2007), a film of a home-rigged laundry line that reels in and out the British, Hong Kong and mainland Mainland china flags that signalled handover or takeover, according to ane's citizenship.

Seen in context, even the better-known work re-engages: the titillation triggered by solo presentations of the 1995 filmed nude operation past Rong Rong and his pioneering Beijing E Village group, To Add together One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain, reverts here to the existential absurdity of naked artists piling on peak of each other to attain a perverted officialdom's directive. Joined hither by a cartoon, a Cai Guo-Qiang gunpowder video showing one of his crowd-thrilling explosions links the ancient Chinese invention to the blowout of the 2008 Shanghai Olympics and America's obsession with blowing stuff upward. Not all are as intelligible. You'll need to report the wall text to know that Wang Gongxin's Heaven of Brooklyn (1995) – which projects the sky of Beijing on to the Guggenheim'south floor – inverts his 1995 photo series, Digging a Hole in Beijing – which streams a tiny video of America's heaven from a abysmal pit – so equally to conflate the Chinese parable of the frog who gained world knowledge from viewing the heaven, with the American metaphor of the hole dug to China (whew!)

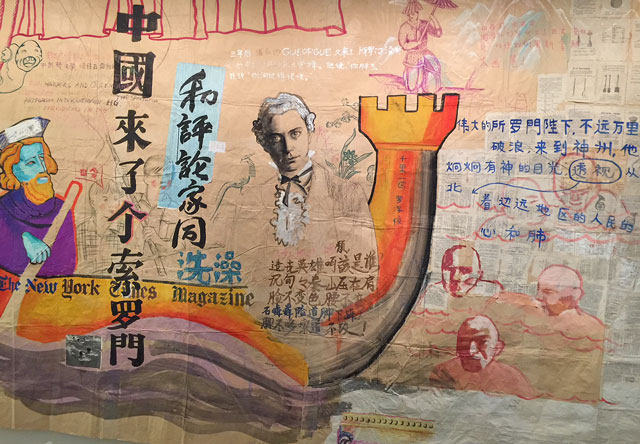

Zhou Tiehai. At that place Came a Mr. Solomon to China, 1994 (detail). 230 x 350 cm. Gouache, oil stick, charcoal and paper collage on packing paper. Photograph: Jill Spalding.

Only the ubiquity of Ai Weiwei feels promotional. Non for his immersive collaborations on behalf of citizens awakened past his Johnny Appleseed sowing of confusing ideas – all elaborately conceived and courageously realised – but for the disproportionate infinite given his oversupply-pleasers. Ai is a conceptual artist, of course. And, yes, he was jailed. But, released through international pressure to wander the planet on silken restraints, he also functions as a semi-gratuitous-will ambassador, tolerated to badger the government, not to topple it. Let him import 1,001 citizens to Documenta in order to document their "dream trip" – as long as he returns them. It jars that running concurrently in New York are more than than 300 public-funded, site-specific and largely agitprop Ai Weiwei installations. And it vitiates the provocation of the solo work given pride of identify here – Ai destroying an aboriginal Chinese vase – to retrieve that he himself was angered by a visitor to the Pérez Art Museum of Miami who held upward one of his vases that was featured there and smashed it to smithereens.

Ai Weiwei. Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn. Installation view: Art and China after 1989: Theater of the Earth. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Oct half dozen, 2017—January 7, 2018. Photograph: David Heald

This show is perhaps too curt on shock – the tactic that then effectively served China'south guerrilla art. The creature travesties duly yanked, it might have included ane of Zhang Huan's or Xiao Lu'southward provocative performances (3 weeks naked in a latrine covered with flies, and shooting an exhibited sculpture with a pellet gun.) Nor is it long on sense of humour – so prevalent in the first wave of Chinese art that had ravished the west. The crackdown was too grim and pushback too earnest. Tiananmen cutting off more than than "free" from the speech. Stop to study Rainbow (1988), Xu Zhen's photograph of a torso, and y'all'll flinch at the clang that accompanies it; Yang Fudong's moving picture of a disaffected denizen'south bumming wander through the "estranged paradise" of Hangzhou stifles all promise, and Yang Jiechang'south instructions above an urn (Testament, 1989-1991) – One Day I Die An Unnatural Death Then One Should Feed Me to a Tiger and Keep its Excrements – veers to the morbid. Fifty-fifty the rare bursts of levity are charged. In that location Came a Mr Solomon to China, Zhou Tiehai'due south cheery delineation of the storied American writer Andrew Solomon, touring on a gondola manned by Marco Polo, wryly links local artists' fading hope for western recognition with the author's all-likewise-brief interlude from his noted battles with depression; and the cute plastic toys flooding in from the world's Chinatowns that furbish Xu Tan's object-laden Fabricated in Cathay manifesto (1997-98) link his nation's new wealth to the detritus that is choking the oceans.

Then much for Mainland china: What virtually the art? The question answered last twelvemonth in contemporary Chinese art shows at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris and Al Riwaq in Doha is non explicitly addressed hither. Ignoring artist pushback against being labelled either "provocateur" or "auction-darling", the curatorial focus on reactive work marginalises no-agenda creativity. No dancer, farmer-sculptor or rice-paddy painter: No thing, art is a vocalization that can't be stifled, and the voices here ring loud and articulate.

Given that Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim is an echo sleeping accommodation, the decision to confine most of the sound pieces to headphones was a wise 1. Just equally astute, to allow a lone, rhythmic throb to suffuse the unabridged exhibition – from where it emanates constitutes a finale of sorts.

Gu Dexin. Installation view: Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, October vi, 2017—Jan 7, 2018. Photograph: Jill Spalding.

The official finale, 2009-05-02, a frieze of 35 panels blood-red-inked in the Communist party's signage by Gu Dexin (held the censor of his generation), accuses all humanity of killing children, eating hearts and beating people blind. Inadvertently coinciding with Xi Jinping'due south self-congratulatory, 205-minute State of China speech to the party congress that submits – four decades after the reform era – all reform to absolute censorship, it simply equally inadvertently places Armstrong'south gesture on a pedestal of decency and good will.

Thankfully, what goes upwards must come down. The Guggenheim's spiraling descent is pure glamour, so permit the long wait for an elevator incline you to walk it and build your own finale. Gestural or minimal; isolated or grouped, written, painted, filmed or constructed, the components marking this alien culture's individual extremes at present menses together, like Chen Zhen'southward (Sharp Parturition, 1999), a fifty-pes-long inner-tube dragon that connects the rotunda, into a polymath artful unified by one longing, i need.

Source: https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/art-and-china-after-1989-theater-of-the-world-review-guggenheim